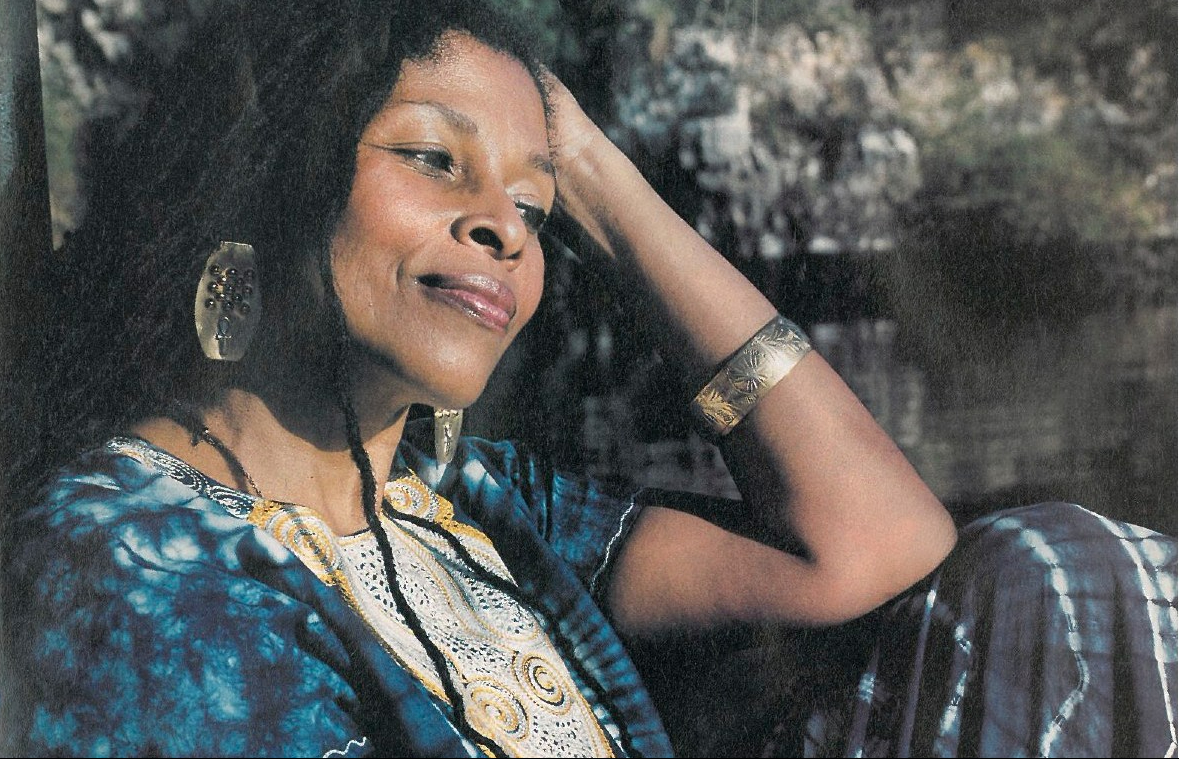

During my junior year of college, I joined a few Black/African organizations on campus; one of the orgs that I joined was the university’s chapter of the NAACP. At the conclusion of our first meeting, we practiced one of the club’s traditions: the students form a large circle, hold hands, and chant the following Assata Shakur quote three times, each time with increasing volume and intensity:

It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and protect each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.

I grew to love the chant and the tradition. I also found the fact that our chant was echoing loudly throughout the student center of an ultra-conservative PWI, moderately amusing.

The third line, “We must love each other and protect each other,” gained significant meaning for me a few months later, during the aftermath of the 2016 Presidential Election.

I watched the election results with a friend of mine who had joined NAACP with me. We were also texting back and forth with other organization members as we all watched the results. In our group chat, there were so many awful emotions: shock, anxiety, anger, fear, despair. People were afraid for many reasons, among them the fear of the consequences of being not-conservative and not-White on a conservative, White campus.

Some of our fears came true.

Supporters of the president-elect showed up at a post-election demonstration on campus and intimidated protestors with racist/xenophobic chants. There were also a couple incidents of physical harassment (the election results had given racists a type of boldness I’d never seen). In perhaps the most infamous of these incidents, a Black girl was walking to one of her classes and was shoved off the sidewalk by a White male, who told her “N*ggers aren’t allowed on the sidewalk.” Someone else intervened and chastised his behavior, but the White male responded, “I’m just trying to make America great again.”

Without a doubt, it was a frightening time to be Black/POC on campus. But then I witnessed the wonder of solidarity.

News of the incident went viral on campus and got the attention of our organization. Within a day, NAACP had already organized on the girl’s behalf. The plan was to have members of the organization, as well as the other Black organizations, show up at the conclusion of the girl’s first class and walk with her, on that same sidewalk where she was harassed, across campus to her next class as a show of love & support, unity amongst the Black students, and, most importantly, protection against any other forms of assault against minorities.

The idea was conceived and organized almost entirely by some of the Black female leaders of our organization. They had built a coalition of not just Black students, but other POC and White students, as well as professors, coaches, deans, and journalists. A crowd of several hundred people showed up to march with the girl to her class all the way across campus. It was beautiful.

I observed two important things that day: 1.) Black women are absolutely sensational leaders and organizers who deserve so much credit for their amazing work and for being the heart and soul of so many movements; and 2.) Assata Shakur’s words were more than just a part of a chant; they were a philosophy of mutual love, support, and togetherness amongst Black people/POC/allies that I was seeing being lived out in person. It truly was a powerful modicum of inspiration in the midst of a very distressing time.

Leave a comment